Exploring a Possible Alzheimer’s Cure With Immunotherapy

An increasing number of scientists and drug developers are turning to immunotherapy – an experimental cancer cure – in the quest for a cure to Alzheimer’s.

It began when Gordon Van Slyke realized he could no longer remember each and every hole on many of the 50 sprawling golf courses in his retirement community just outside Orlando, Florida. This would be an extraordinary feat for most people, but for Van Slyke, an avid golfer who prides himself on memorizing not only every hole but also the precision of each shot that goes with his game, it was his norm.

“It was the first serious warning sign.” he said.

At 73 years old, Van Slyke has recently been diagnosed with early stage Alzheimer’s disease, but in some ways, he feels lucky as his loved ones with the disease died at younger ages: With a strong familial link to the disease, both his mom and sister died of Alzheimer’s while in their sixties. “My mom got so bad the doctor told us she died because she forgot to breathe,” he said.

Understanding that an Alzheimer’s cure may not come in his lifetime, Van Slyke felt he needed to do something — for his two sons and four grandchildren. He saw an ad in the local newspaper for an Eisai study of a new investigational medicine that may not only treat symptoms of Alzheimer’s, but it could also potentially be disease-modifying. After Gordon responded to the ad, he learned that it was a trial for a drug known as an immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy is the prevention or treatment of disease with drugs that stimulate an immune response. Scientists are looking for a cure to Alzheimer’s disease that boosts our immune systems. Administering drugs to elicit an immune response works in a similar way to a vaccine and pharmaceutical companies are placing bets on immunotherapy to target Alzheimer’s disease.

“I think it would logically follow with the success with cancer with other immunologic diseases that there will be some success with this,” Dr. Jeffrey Norton, a principal investigator at Charter Research, told Being Patient.

Researchers have used immunotherapy to tackle certain cancers, from lung to skin, but they are now tested it in phase III clinical trials to target neurodegeneration. Big pharmaceutical companies like Eisai and Biogen are investing heavily in immunotherapy, testing in human trials the drugs BAN2401 and Aducanumab respectively.

A Cure For Cancer, So Why Not Alzheimer’s?

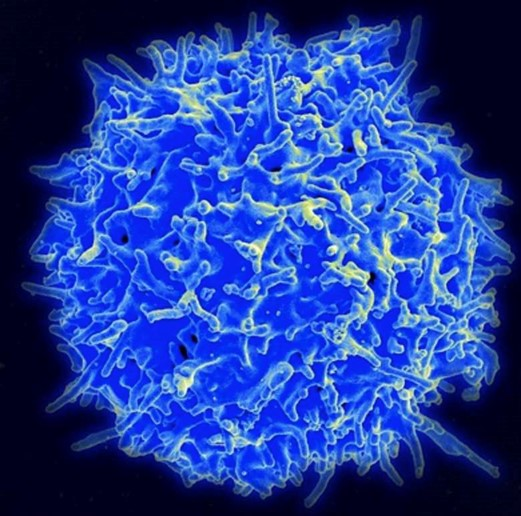

In 2018, two scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine for their separate research on activating the immune system to attack cancer. A breakthrough discovery, the work of Dr. James Allison at the University of Texas and Dr. Tasuku Hanjo at Kyoto University in Japan, led to the development of several immune therapies. Both scientists discovered proteins that bind to the T cell, a type of white blood cell that is an essential part of the immune system. These proteins became drug targets for the development of therapeutics that help the immune system identify cancer cells as foreign so they can attack these cells.

In the case of Alzheimer’s, immunotherapy is based on the same principle: Molecules form antibodies that bind to the toxic amyloid plaques, considered the first hallmark of neurodegeneration. Mouse studies have shown that these antibodies have successfully reduced plaque in both the hippocampus and cortex regions of the brain, the two areas of the brain most impacted by Alzheimer’s disease. Despite the fact that most mouse studies don’t translate into human success, scientists remain hopeful that the same proven theory for cancer will work to prevent and treat neurodegeneration in humans.

How Do Immunotherapy Drugs Work?

For decades, scientists have been targeting amyloid plaque to unlock the mystery of an Alzheimer’s cure, but this approach has, so far, been unsuccessful. For many brain disorders including Alzheimer’s, scientists haven’t identified the disease’s root cause, and that makes identifying drug targets more challenging. But because of immunotherapy’s success as a cancer treatment, scientists and drug developers believe it has promise.

Immunotherapy drugs targeting Alzheimer’s are biological products made from human or animal cells that can mimic a patient’s immune system and produce antibodies to fight the production of amyloid plaque. Unlike a vaccine, these are not administered just once or twice; rather, treatment is repeated over months or years, allowing an immune response to prevent the formation of plaque in the brain over time.

Scientists have yet to prove whether immunotherapy can stimulate the infiltration of immune cells that would fight both amyloid plaque and inflammation. Researchers are also trying to understand how effectively these medications can cross the brain blood barrier (BBB), a border of endothelial cells that protect our brains.

“The idea would be, can you slow or stop that process? And if so, does that translate to a change in the disease as it manifests clinically?” Norton said.

What Is It Like to Be in an Immunotherapy Drug Trial?

Often, a drug trial will recruit an elderly population of people who are in the earlier stages of memory loss. For example, a current phase III trial by Eisai is recruiting patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or early stage Alzheimer’s disease and have the presence of amyloid plaque in the brain. Each participant will be given a comprehensive screening that includes cognitive testing, MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. The drug is administered intravenously every two weeks. Patients are given either the drug or a placebo, but the placebo cohort will be given the drug for six months after the trial.

For Gordon Van Slyke, it means a trip to his nearby clinical trial center, where he gives urine and blood samples and then receives an infusion of the immunotherapy drug every two weeks. “It’s really just like having a job,” Van Slyke said of the recurring trip to the trial center that will last for the next twelve months. After six weeks in the study, he says he has had no side effects.

“I have the legacy of family with my kids and grandkids,” Van Slyke said. “My genes are part of them, so I owe it to them to help find a cure.”