The Role of Mitochondria in Alzheimer’s

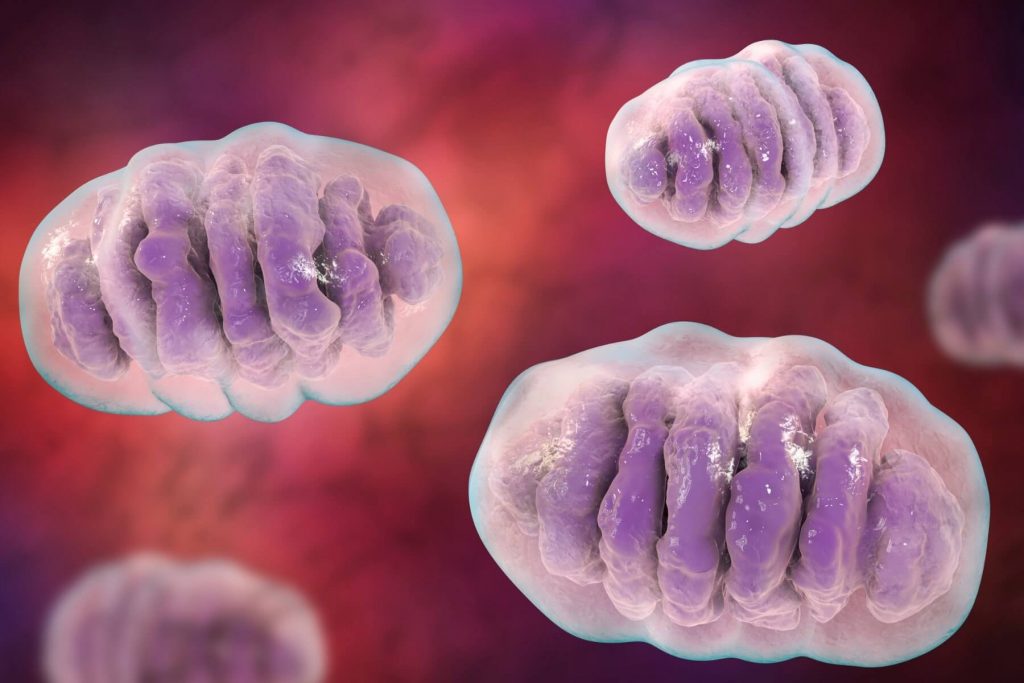

Despite accounting for two percent of our body weight, the brain consumes 20 percent of the body’s energy. Driving that energy production are our mitochondria: factories within brain cells that convert oxygen and glucose fuel into energy, keeping the cells healthy. This process is called bioenergetics—crucial for keeping brain cells healthy. But as we age the mitochondria begin to break down, making it more difficult to keep brain cells healthy and even contributing to Alzheimer’s.

When do mitochondria break down?

A powerhouse can get overloaded when there is too much electricity flowing through it. Similarly, amyloid plaques in the brain dysregulate calcium, which plays an important role in learning and memory. Dysregulated calcium is left free-floating in the neuronal cell and then overloads the mitochondria. Like an overloaded powerhouse, the mitochondria can no longer produce the same amount of energy.

Even if the powerhouse is running, obsolescent machinery can make it inefficient. And that may be part of the reason that in Alzheimer’s, it seems the mitochondrial damage may happen even faster, rendering the powerhouse of the cell incapable of providing energy for the brain.

In Alzheimer’s mitochondrial dysfunction, individuals affected by the disease are less efficient at producing and harvesting energy. Their mitochondria may have less protein machinery, making it harder to generate the same amount of energy. Changes in the blood vessels that bring oxygen to the brain are another common consequence of the disease, that reduces the total amount of energy that can even get there.

Even when there is plenty of fuel, it needs to be fed into the power generator—this is where insulin becomes a necessity.

Insulin resistance, a condition associated with diabetes, is another risk factor for Alzheimer’s that contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction. In the brain, there is a reduction in insulin levels making it more difficult for cells to take up glucose and turn it into energy. There is already evidence from studies of obese and pre-diabetic adolescents that administering insulin improves cognition.

When cells don’t produce enough energy, they can’t send their electrical signals. These impairments can then affect a person’s cognitive ability, in addition to slowly killing the cell itself. Amyloid plaques might speed up the process by overloading mitochondria with calcium. Inherent deficiencies in energy production and harvesting then have a cascading effect on the brain, leading to more and more degeneration.

What can mitochondria tell us about the future of Alzheimer’s treatments?

Could targeting the mitochondria and bioenergetics of Alzheimer’s disease lead to new treatments?

After the failure of a mitochondria-targeting drug called dimebon, there haven’t been any new drugs developed to target the pathway. For now, lifestyle changes, like eating the Mediterranean diet and getting enough exercise, are valuable preventative measures for Alzheimer’s that also help make sure our brain cells have the power to help stave off the onset of the disease.

To learn about clinical trials of new medications that aim to modify the pathology of Alzheimer’s disease, call Charter Research at 407-337-1000 (Orlando) or 352-775-1000 (The Villages).